Friday Night Science: Why Aren't There Any Square Planets?

Ever wonder why planets are round and not square? Pringles chips? Or like donuts?

Well, here's the thing. Planets are round because that's how gravity works. Earth's gravity, or gravity for the matter, pulls equally on all sides. It doesn't matter if you're at the North Pole or hanging upside down from the South; Earth always pulls you towards its center.

If you go to Mars or the Moon, Jupiter, or Saturn, the effect of their respective gravities on you will be (much) the same. Of course, the Moon, weighing only one-sixth of Earth, will pull you less, and what’s more, you’ll weigh three times less! That’s why Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were jumpy. Jupiter, the colossal giant weighing over 318 Earths, has 25 times the latter's gravity. If the gas giant had a solid surface for you to land on, you’d feel 25 times heavier! But that’s just planets. Across the vast infinite expanse of our universe, some stars make you feel a million to a billion (which is one followed by six and nine zeros, respectively) times heavier. If you think that’s the ultimate limit, then wait till you pass a black hole — near the event horizon of a black hole (which marks the point of no-return), gravity can be a trillion times strong (one followed by twelve zeros) — and beyond the event horizon, gravity shoots through infinity!

Gravity is the force by which every literal speck of matter attracts every other piece. Earth pulls the Moon — Moon pulls Earth — and together, they pull the Sun, only to be tugged in return. All members of our solar system, planets, their moons, asteroids, comets, planetary dust, and all the star systems beyond our immediate neighborhood, scattered in a numberless multitude of galaxies out there, have this innate property. More so, between you and me, though we are miles apart, separated by the Atlantic perhaps, we’re drawing each other through gravity.

So far, so good. Gravity attracts. Gravity pulls equally. But why’s Earth round?

When the Earth was born, it was like pizza dough. Soft, squishy, and jiggly. Molten on the inside, filled with sticky lava. So were the other planets. Since gravity pulls matter towards the center, introducing a new term, center-of-mass, like spokes on a bicycle pointing from the edge towards the center, planets in the three dimensions of space come out as spheres. Planets form by the accretion (clumping) of gas, dust, and dirt over time. In the beginning, they all start out irregular. But as more and more matter clumps together, their gravity gets stronger. When such a planet gets massive enough, it gives way to its own gravity. Its insides turn to lava. At this stage, its self-gravity (another term worth keeping in mind) adds the final touch. Pulling all matter towards the center, the irregular hunk of a planet smoothens into a sphere.

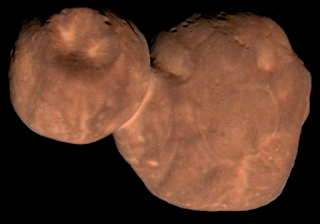

Asteroids and comets are oddballs because they aren’t massive enough for their self-gravity to shape them into spheres.

Now, the final thing. If gravity can form spheres, then why not cubes? The answer lies in the geometry of a sphere and a cube. A sphere has perfect symmetry, meaning no matter from what side you’re looking, a sphere appears the same. All points on the surface of a sphere are equally distant from its center of mass since we’re talking about planets. A cube, on the other hand, has corners. A corner point is farther away from its center of mass than a point on one of its six faces. As such, corners would be more massive, and going down the rabbit hole, even if an advanced alien civilization assembles a cubic planet, gravity will eventually smooth out the sharp edges and form a sphere.

In summary, planets can’t be anything other than spheres because gravity pulls matter equally on all sides, which in the three dimensions of space results in a sphere. A sphere is the most symmetrical shape there can be. Nature has an affinity towards symmetry. Any irregularities will cause an imbalance, a break in symmetry that gravity doesn’t allow. And so, no cube planets, prism planets, and two-dimensional tortilla planets, but spherical orbs.

See you next Friday. In the meantime, try a potato!

Comments

Post a Comment