Once In a Blue Moon?

What's that expression - Once in a Blue Moon? Our nonchalant way of describing something that rarely happens - like meeting your distant-land cousin or winning a million-dollar jackpot. What does Earth's natural satellite have to do with the winning numbers?

The answer's nothing. The Moon has no occult properties to turn the odds on you. Winning that jackpot is only a matter of probability and what appears to be luck. A Blue Moon refers to the second full Moon in a calendar month. That's what we all know. But - and a long pause after that - there's more to it. The blue Moon has a long and winding story dating back a few hundred years when time-keeping was being standardized. The bleue Moon's origin story has a lot to do with calendars and almanacs. The latter is a type of publication containing meteorological and astronomical data and a plethora of stuff you can think of. Such a story deserves a singular article. For now, I'll have to hold it. Instead, I'll throw the spotlight on a different character. Can the Moon be blue?

But before that, where does this extra full moon come from? One lunation, i.e., the Moon's waning from full illumination to zero illumination at new moon and then wax up to full moon phase, lasts 29.5 days. Twelve full moons, one for each month, add up to 354 days, 11 days short of a complete year. Just as the discarded bit at the end of every calendar year adds up to a 29th day for February every four years, the 11-day mismatch between a lunar year and a calendar year adds up to an extra lunation every 2.5 years. This 13th full Moon is popularly known as the Blue Moon.

Even though we talk of a blue moon, of all things, the Moon is anything but blue. It's never orange, green, yellow, purple, or whatever. And no, it's definitely not blue cheese.

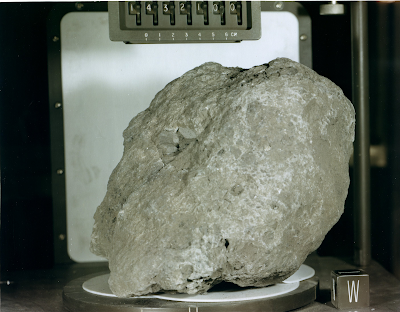

For those who have been fortunate enough to be on the Moon, the Apollo astronauts, and the scientists who've tinkered with the lunar rock samples brought back here on Earth, they know for sure that the whitish-silvery orb out there is very grey. Our celestial neighbor has an albedo, the percentage of incident light any surface reflects, close to that of old asphalt. Luna shines bright in the night sky simply because of two factors - its close proximity to Earth - and its sheer size. Because of tidal locking, the Moon points the same face towards Earth. At any time, during a full moon, we're looking at 59% of its total surface area of about 38 million square kilometers or 14.6 million square miles. So forth, when the Sun rises over the lunar landscape, even the dullest and the grayest terrain appears bright against the blackness of space and the open night sky.

|

| One million miles away in the direction of the Sun, NOAA's DSCOVR satellite captures this one-of-a-kind photograph of Earth and the Moon with the latter's far side basking in unfiltered daylight. Concomitantly, during a lunar eclipse, the far side of the Moon receives the full blast of the Sun while the always-seen near side descends into darkness. As captured in true color, the lunar topography appears visibly gray. Image Credits: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. |

A misconception often arises that the far side of the Moon, more popularly the dark side (Pink Floyd has an album named The Dark Side of the Moon), remains in perpetual darkness, shielded from the Sun. Well, there are places on the Moon, near the poles, that have never seen sunlight in 4.5 billion years, all likely. Moon's polar axis is almost perpendicular to the direction of sunlight. These Permanently Shadowed Regions have stayed and will stay under the blanket of never-ending darkness - they are an enigma in their own right. But the dark-side of the Moon, i.e., the far side, is not dark at all. Earth-Moon tidal locking does not mean our natural satellite remains affixed to one particular spot. Like its partner, Earth, the Moon also rotates on its axis. However, by the time it gets to turn on its axis, for once, it finishes its orbit around Earth. Moon's orbital and rotational periods amount to 29.5 Earth days. That is to say, a day on the Moon lasts as long as a lunar year. Therefore, we are always seeing the same face. If the Moon were stationary, we would've alternatively seen its far and near sides while it circled Earth.

|

| If not for tidal locking (left), the Moon would alternatively show its near and far sides (right). Image Credits: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. |

As photographed by multiple spacecraft, landers, and even humans, the far side presents a more rugged topography imbued with numerous craters. Battered down for 4.5 billion years by an onslaught of countless meteoroids, the far side appears leprotic, in contrast to the smooth Maria on the near side. Early astronomers mistook the volcanic lava plains for seas and thus the name Maria (sing. Mare). Basaltic rocks, being very rich in iron, have a lower albedo. This is why the lunar mare presents darker than the surrounding highlands made of igneous rocks (molten lava but the kind that cools slowly). To see its true colors, one has to be there, walking on the surface, picking up dust and rocks. Moon's actual color depends entirely upon its mineral composition. All in all, the Moon reflects an off-white to brown-gray light.

If the Moon is gray, then what's with the blue moon? Congratulations! Perfect guess. It's never blue. But there's a catch. How we earthlings see the Moon depends on our planet's atmosphere. On chance days, the Moon may turn pink, green, red, yellow, and what you'd least expect, mauve. Light, it turns out, when traveling through the atmosphere, interacts in myriad ways with the very constituent atoms and molecules of nitrogen and oxygen, carbon dioxide and water vapor, and all the other gases. Dust particles, pollen grains, soot, and with all seriousness, even our farts play a vital role in altering how we see the Moon.

Once you start observing the Moon on a regular basis, within a few days, you'll notice that the satellite doesn't always appear silvery-white. When it's not yet above the horizon the Moon appears alienly red. As it rises, that is to say, while its elevation angle increases, its color shifts from red to orange to yellowish, and finally, it regains its semblance as it climbs to its highest point in the sky (zenith). There's only one explanation for this - Rayleigh Scattering - the same scattering of sunlight via atoms and molecules in Earth's atmosphere that pertains to the blue color of the daytime sky and turns the Sun bloody-red at sunset/sunrise. The Moon shines by reflected sunlight. Therefore, bouncing off the lunar surface, sunlight, as it passes through Earth's atmosphere, suffers Rayleigh scattering, which strips off the bluer wavelengths, leaving behind yellow, orange, and red. When the Sun is almost setting or the Moon is about to rise, their lights travel through a considerable length of Earth's atmosphere. This is simply because when they're directly above our heads, their light reaches us through what can be best described as one-atmosphere length of air. Since the Earth is always spinning, closer to the horizon, the Sun or (reflected) moonlight has to cross a greater length of the atmosphere. Earth's gradual turning away from the Sun or Moon lengthens their optical path as they graze the surface tangentially rather than dropping down perpendicularly. Traveling tangentially through this increased mass of air (~40 times) completely removes the blue wavelengths, turning the Sun/Moon red while they're just over the horizon. Higher up in the sky, when their light travels to us almost perpendicularly through one atmosphere of air, Rayleigh scattering becomes less dominant, and the Moon looks as usual.

Forgetting blue moons for a while, Rayleigh scattering, on a particular occasion, results in an ominous Blood Moon. Just like blue moons have no meaningful correlation (and abject proof) with men transforming into vicious werewolves, with their perfectly polished ass metamorphosing into a hairy mess, and entire townspeople going loony and hanging themselves upside down, a Blood Moon does not portend the fall of kings (in modern times the fall of democracies) and the coming of death, pestilence, and bloodshed.

A blood moon happens during a lunar eclipse. When the Moon fully enters Earth's umbral shadow, no direct sunlight illuminates the lunar topography. However, some indirect sunlight, transmitted and refracted through Earth's atmosphere, reaches the lunar scope. Since this refracted sunlight becomes deeply reddened due to Rayleigh scattering, the otherwise-silvery Moon turns ruddy red - the color of blood. A ''Blood Moon'' is not a scientific term but a catchphrase for a total lunar eclipse. The degree of redness depends on Earth's atmosphere and the suspended particles.

|

| Blood Moons are nothing to fear. Just a trick of Earth's atmosphere. Image Credits: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. |

If the Moon ever appears blue, it means too much smoke and dust particles are in the atmosphere. On a global scale (mind it), a blue moon may appear blue in the event of a massive volcanic eruption. On a local scale, in the wake of a major forest fire, the Moon may acquire a blueish tinge. Only under these specific situations can you have a blue moon. When the Krakatoa, a volcano in Indonesia, erupted in 1883, it spat so much soot, dust, and ash that the Moon completely looked blue and on certain days, even green. If the size of the scattering particles turns out to be ~1 micron, the red light will get strongly scattered while the blue and green wavelengths pass undisturbed. Since major volcanoes are sound sleepers, themselves waking up once in a blue moon, to make it more fitting, you can say, ''Once in a super-volcano comes a blue moon''.

|

| In the wake of a major wildfire or a catastrophic volcanic event, smoke and soot particles may turn the Moon blue. But only to an extent - sort of an Egyptian blue shade. Image Credits: Public Domain, via www.flickr.com |

Different kinds of particles - soot, pollen, water vapor, dust, single-celled bacteria - floating in the air induce degrees of scattering. On this accord, the Moon may sometimes look blue, green (due to pollen), pink, and even violet, not to forget red, yellow, and orange. If you go on to this NASA page - you'll see someone has brilliantly photographed the Moon in its myriad shades. While some particles scatter blue light, leaving behind red, others do the opposite, turning the Moon blue. Martian dust is of such size that it scatters away red light during sunset/sunrise. As such, future Earthlings on Mars would wake up to blue dawns and bluer dusks.

To say a bit more about Rayleigh scattering, the azure blue of Earth's daytime sky is a haze. This becomes apparent when you try to look at the Moon during the day through a telescope (but don't turn that thing to the Sun without having proper filters!!). Looking through the eyepiece, the daytime Moon appears slightly bluish. At the same time, if you were to go to space, 100 miles or higher above the surface of the Earth where the atmosphere is, the lunar landscape would loom before you with its gray and grayer mare. So that's Rayleigh scattering.

Comments

Post a Comment