DEEP SKY OBJECTS IN ORION - THE FLAME AND THE HORSEHEAD NEBULA

Galileo never came up with the idea of a telescope, contrary to much popular belief. He naturally followed up on a Dutch glassmaker's, Hans Lipperhey or something close, novel contraption involving a pair of lenses which, to the inventor's surprise, made distant objects appear as if nearby. Galileo's name stuck with the telescope when he turned the instrument of his own making towards the Moon and discovered a world unto itself. What appeared as a single planet, the mighty Jupiter, was suddenly seen to have four little followers, whereas Saturn appeared with ears. Had there never been telescopes or binoculars, astronomy would have reached a fundamental limitation, the human eye. Marvellous it is, yet, our eyes are not something we can use for doing astronomy. Of course, much of the subject developed at a time when there were no telescopes. Hipparchus created his famous star catalogue by looking at the unpolluted night sky, littered with thousands of scintillating stars. But that would have been it. We could only know that the anthropo-sympathetic Sun is close, the Moon closer, the planets far though not so far, and the stars distant. Luckily history notes otherwise. With state-of-the-art, multi-wavelength, space-based or fixed-on-the-ground-type telescopes, with single mirrors, multiple mirrors and interferometry, we are able to see the universe in ever-increasing detail.

Much like that, in the context of our continuing article, the familiar outline of the Orion constellation reveals itself as a seemingly large and quite intimidating cosmic structure known as the Orion Molecular Cloud Complex. To prevent my website from crashing, I am uploading a low-res photograph with a link to the source where you can see the original image.

The Orion Complex is a star-forming region, an active stellar nursery, a silver of which can be seen with our bare unaided eyes when looking towards the Sword. The small patch of nebulosity, seen more or less at the middle of the blade, is the famous M42 nebula or what is also known as the Orion nebula. In long-exposure photographs, the same patchiness reveals the identity of another popular target, i.e., the M43 nebula. Along with some other kinds of nebulae, dark nebulae, reflection and emission nebulae, the apparently empty space around the prominent asterism of the Sword forms a part of the molecular complex known as the Orion A molecular cloud. The greater association of the complex involves other regions of stellar activity, namely the Orion B molecular cloud located east of Alnitak. Apart from these two major star-forming regions, the three stars of Orion's belt, plus some other star clusters to the north and south of the belt, find themselves within the Orion OB1 association. The OB1 association consists of additional subgroups and clusters of O- and B-type stars. The relatively small patch of sky around Lambda Orionis or Meissa contains another molecular cloud, also known as the Lambda Orionis Molecular Ring. The giant star, 𝜆 Orionis, ionises the surrounding molecular medium and thereby causes it to glow red, respectfully earning itself the name of what in the standard scientific jargon is called an H II region. Finally, to complete the picture in the above photograph, we can see a giant filament of molecular gas arching across the eastern plane of the constellation. That is the Orion-Eridanus Superbubble (more on this later).

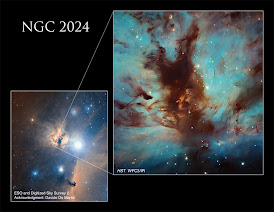

For our present article, we will concentrate on the left side of Alnitak, on two of the frequent targets for amateur as well as professional astronomers. They are the Flame Nebula (NGC 2024), the Horsehead Nebula and IC 434, a multiple-star system that goes by the name Sigma (𝜎) Orionis, finally ending with M78, another famous nebula.

Let us begin with a deep-sky photograph of Orion's Belt. From the image below, one can clearly make out that the bright white star more-or-less at the centre of the field-of-view (fov for short) is Alnitak, while the equally bright star at the extreme right corner is Alnilam. Mintaka is outside the fov. The Flame Nebula is the dark filamentous patch sticking out to the left of Alnitak. The Horsehead nebula marks its place below Alnitak, protruding towards 𝜎 Orionis, the blue-white star on the lower right of the fov.

|

| Deep Sky view of Orion's Belt showing the interstellar region around the Flame and the Horsehead nebulae. Image Credits: ESO and Digitized Sky Survey 2 (full res image link). |

By merging the data of individual photographs taken across x-ray and infrared wavelengths, astronomers have recently found that stars in the central region are at a young age of 200,000 years old and those on the outskirts are older at 1.5 million years. x-ray data taken by the Chandra Observatory reveals a large population of pre-main sequence stars. Since x-rays pass unobstructed through the dense gaseous filaments opposite to visible light that scatters away heavily due to the high concentration of gas and dust, in the Chandra image, the individual stars come out as purple pinpricks against a dark background. A set of infrared images taken by the Spitzer, 2MASS, and the UK Infrared Telescope illustrates the intricate structure and the ebb and flow of gas. As Hubble (HST) zooms into the dark deep of the Flame Nebula, we can identify the swirling distribution of gas. The blue-green glow of the surrounding medium occurs due to the ionisation of the interstellar molecular medium, which invariably confirms the presence of hot young stars. Young stars, particularly massive ones, emit copious amounts of ultraviolet radiation, including x-rays, as they excessively devour their store of hydrogen. The excessive emission of high-energy radiation breaks apart molecular hydrogen into free hydrogen ions. A particular scheme of ionisation called the H II ionisation, i.e., where H₂ is doubly ionised, illuminates a typical molecular cloud in brilliant shades of red and vermilion. In a similar manner, blue and green shades mark the characteristic signature of helium and oxygen, respectively.

|

| Pre-main sequence stars in NGC 2024 appear as purple pinpricks. Image Credits: Chandra X-ray Observatory |

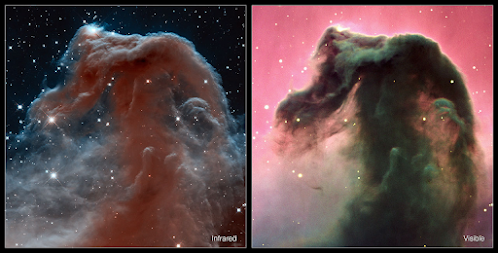

Set aside the dark filaments, the Flame Nebula is an emission nebula at a distance of about 900 - 1,500 light years away. The Horsehead Nebula, on the other hand, turns out to be a fine specimen of a dark nebula. A dark nebula or absorption nebula is so dense a molecular cloud that it almost completely blocks out the passage of visible light, thereby effectively concealing whatever lies behind it. The Horsehead is so named because when we zoom in and rotate our fov by 90 degrees, what we get, appears very much like the head of a lovely sea horse, rising upwards as a dense column of gas silhouetted against a crimson-red background.

|

| Hubble's view of the Horsehead Nebula across infrared (left) and visible (right) bands. Image Credits: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (AURA/STScI); ESO |

IC 434 is an emission nebula glowing crimson-red from the strong H𝛼 emission line of ionised hydrogen (H II) at 656.3 nm because of the energetic radiations let out by 𝜎 Orionis.

|

| The mosaic image, patched from photographs taken through the standard Red-Green-Blue bands of the visible spectrum, along with data input from specific filters of H𝛼 (H II ionisation, red) and O III ionisation (teal), covers the entire region of IC 434, the Horsehead and another reflection nebula, NGC 2023. Image Credits: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons (link). |

|

| NGC 2023 takes on a milky appearance, illuminated by its central star. Image Credits: ESO (high-res link). |

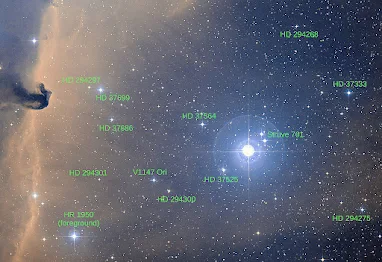

Staring at the constellation, what appears as a bright star immediately south-west of Alnitak is a gravitationally bound quintuplet system of very young stars located some 1,100 to 1,200 light years from the Sun, all under the age of 3 million years and shining brightly across the main sequence. Together, they also take their fair share in illuminating IC 434. The primary member, i.e., σ Ori Aa, is a spectroscopic binary lodged in a tight orbit with σ Ori Ab. Their separation ranges from 0.5 - 2 au (1 au equals roughly 150 million km). σ Ori Aa is a massive O-type star weighing around 18 solar masses, and with a surface temperature above 35,000 K, it shines blue-white with the combined luminosity of 41,000 Suns. It is also approximately 5.6 times larger than the Sun and possesses a rotational velocity of 135 km/s. Its spectroscopic pair, σ Ori Ab, is similarly heavy at 13 solar masses, having a surface temperature higher than 31,000 K and glowing blue-to-white at 18,600 solar luminosity. It is about 4.8 times larger than the Sun and spins moderately at 35 km/s. The Aa/Ab pair has a close visual companion, σ Ori B, supposedly a B-type main sequence star. Invariably, it is 5 times larger than the Sun, weighing 14 times more and having a surface temperature close to 29,000 K, a luminosity 15,800 times great and spins rather swiftly at the rate of 250 km/s. Five of the brightest members of the cluster are labelled from A to E based on their distance from the massive primary σ Ori Aa. As such, σ Ori C lies at a separation of 3,960 astronomical units from the AB system. It is an A-type star nearly 3 times more massive than the Sun. Finally, σ Ori D and E are B-type stars, both bulkier than the Sun and like C, they have their own fainter components. σ Ori E has interesting magnetic properties and spectral signatures, and astronomers are looking more into this unusual star. Apart from the above five, the σ Orionis cluster crowds together other gravitationally bound stars.

|

| σ Orionis cluster in visible light. The Aa/Ab spectroscopic binary pair appears unresolved as a single bright object. Image Credits: Public Domain (high res link), via Wikimedia Commons |

The last thing we will see before dropping the curtain on this article is the Messier 78 or the M78 reflection nebula. M78 lies some 1,350 light years from the Sun and is part of a spread-out collection of other reflection nebulae NGC 2064, NGC 2071, and NGC 2071. M78 spans over 5-light years across, tucking away dozens of protostars that are yet to go a long way before becoming full-fledged main sequence stars. The reflection nebula gets its characteristic luminosity from the intense radiation of two massive B-type stars.

|

| NGC 2071, NGC 2067, M78, and NGC 2064. Image Credits: Public Domain (link), via Wikimedia Commons. |

Unless the night sky is free from all sources of artificial lights, with few exceptions, nebulae are almost impossible to see with the naked eye. Nebulae are not compact objects like stars. A typical nebula, not a planetary nebula or the expanding gas layers emanating from a dying star, but a star-forming interstellar molecular cloud complex, i.e., a stellar womb or a stellar nursery as frequently called, can stretch for hundreds of light years. They are nowhere as dense as the best-created vacuum chambers in Earth's laboratories. To put it into perspective, where Earth's atmosphere contains about 10¹⁹ molecules per cubic centimetre, a stellar nursery can have a density of roughly 10⁴ molecules in the same volume. Dark nebulae contain so much gas that they block out visible light radiation and effectively conceal the presence of newborn stars, protostars, protoplanetary discs and stellar jets. When seen through an optical telescope, they appear as deep dark filaments of gas, whose detailed structures can only be revealed by looking through infrared bands of the electromagnetic spectrum. Emission or reflection nebulae, on the other hand, or H II ionisation regions, courtesy of bright hot stars in their cores, puts on an unworldly display of brilliant shades of red, crimson, scarlet, teal, and an unending mixture of colours as the characteristic spectral signatures of their respective elements. Only through long-exposure photographs, like the ones in this article, taken through giant telescopes, we mere mortals can gaze upon some of Nature's magnificent creations. Nebulae can be tens or even hundreds of times more luminous than the Sun. But as already mentioned, the former are diffuse objects and taking their distance into account, not many photons can reach our eyes per second to render them visible just as it is. But the Great Orion Nebula - the ''middle star'' in Orion's ''sword'', is one such (emission) nebula that can be seen directly with the naked eye, even under moderate light pollution.

In the upcoming issue, we will focus on the Orion nebula, the astronomers' delight, professional or amateur, or ordinary folks who love looking up.

Comments

Post a Comment